Archived information

This content is archived because Status of Women Canada no longer exists. Please visit the Women and Gender Equality Canada.

Archived information is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Evaluation of the Women's Program

Final Report

2011–12 to 2015–16

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Purpose

- 2.0 Program Description

- 3.0 Evaluation Description

- 4.0 Findings

- 5.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A: WP Theory of Change

- Appendix B: Evaluation Issues, Indicators and Data Sources

List of Acronyms

- CI

- Continuous Intake

- FTEs

- Full Time Equivalent

- GBA

- Gender-based Analysis

- Gs & Cs

- Grants and Contributions

- SWC

- Status of Women Canada

- O & M

- Operations and Maintenance

- WP

- Women’s Program

- Ts & Cs

- Terms and Conditions

Executive Summary

Overview

Status of Women Canada’s (SWC) Women’s Program (WP) is a grants and contributions (Gs & Cs) program that provides funding to Canadian organizations to support projects that work to advance equality for women in Canada by creating conditions for success for women. Funded projects occur at the national, regional, and local levels and work to address three priority areas: ending violence against women; increasing women’s economic security and prosperity; and encouraging women’s leadership and democratic participation. The WP is a permanent program, with renewal of its Terms and Conditions occurring when required. The program had a budget of $89.6M over the four years under study.

The objective of the evaluation is to provide decision-makers with credible and reliable evidence to inform SWC decision-making about the WP’s future directions. The scope of this evaluation includes all WP activities since the previous evaluation to the present (2011–12 to 2015–16). It builds on the previous evaluation of the WP and considers intended immediate, intermediate and longer-term outcome as articulated in the program’s theory of change. The evaluation addresses issues of relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the WP. To ensure a valid assessment of the program, the evaluation used multiple lines of evidence, including: document, literature and administrative data review; file review; key informant interviews; survey of funding applicants; and case studies.

Key Findings

Relevance

There continues to be a strong demonstrated need for the WP. The program’s focus on violence, economic security and prosperity, and leadership reflects areas where significant gender disparities continue to exist in Canada. Program demand has been strong over the period under study, with applicants indicating program funding to be critical to project implementation. WP objectives and expected results align with the SWC strategic outcome and federal government priorities as outlined in recent federal Budgets and other commitments of the new government. Addressing issues of gender equality is appropriate for the federal government given their national scope and Canada’s commitments to gender equality in domestic laws and international agreements. WP funding is consistent with the efforts of national governments in other industrialized countries to address equality between women and men. While some other funding programs to advance gender equality exist at the national and provincial/territorial levels, the WP is distinguished by its national scope, focus on systemic change and larger, more stable funding opportunities.

Design and Delivery

The WP design and delivery features identified as important in the program’s theory of change are generally in place and contributing to intended outcomes. Funding recipients are satisfied with many aspects of the program’s application process, though identify streamlining the application process, improving timeliness of approval decisions and communications as areas for improvement. Applicants are also sometimes challenged by the program’s partnership requirements and the focus on systemic change, which can deter smaller organizations from applying for funding. Unfunded applicants indicate a lack of feedback on the reasons why their project was not funded.

There are some challenges with delivery that hinder the program’s achievement of its outcomes, particularly the goal of achieving systemic change. The program criteria that have prevented funding of advocacy and research and the three year maximum funding period were identified as detracting from projects’ potential to lead to systemic change. The evaluation gathered other feedback that pointed to the need for improvements in the program’s knowledge dissemination efforts.

Effectiveness

The WP is achieving its intended immediate outcome of creating supports to address issues relating to gender equality, with funded projects developing a wide and diverse array of tools and supports in each of the pillar areas.

Ensuring that communities and stakeholders have access to opportunities to use or apply the tools and supports – the program’s intermediate outcome – is being partially achieved through dissemination of projects’ tools and supports. Projects use a variety of channels to disseminate their products, with a significant focus on web-based methods and social media. While most projects continue to make their products available after the WP funding ends, there is no central repository for sharing products more broadly beyond the project’s own partners and networks.

Partnerships at the project level are key to transferring project products and sustaining their diffusion at the end of funding. Evaluation evidence suggests that projects have been diligent and successful in establishing numerous and diverse partnerships in the design and (more frequently) implementation phases of their project. Funding recipients report that partnerships often outlive the project, as they continue to work with partners on other endeavours.

In terms of addressing the program’s longer-term outcome – communities and stakeholders advance equality between women and men – a significant proportion of projects (between one in three and four in ten) were sustainable beyond the WP funding and reported systemic change as a result of their project through operational, policy or practice changes that foster gender equality (although it is difficult to quantify the magnitude or significance of these changes).

Projects typically identify the capacity of their organization, partnerships and WP funding (though less often guidance and support from the program) as facilitating factors of their success, while the key factors that are viewed as inhibiting project success are the complexity of the systemic barriers they are trying to address and institutional resistance to change.

Intersectionality has increased in importance, both for the WP and its stakeholders. While a GBA+ approach does pose challenges for how the program is positioned in comparison to other federal partners, the organizations funded by the WP view the ability to account for multiple barriers as a key factor in facilitating project success.

Efficiency

The cost to SWC of delivery $1 of Gs & Cs funding is $0.19, which has increased compared to the previous evaluation which calculated the cost of program delivery to be $0.13 for every $1 granted. A high number of calls for proposals and announcements during the study period, the priority during recent calls to reach out to new groups and to fund more demanding initiatives leading to systemic change translated into additional workload for staff which, together with investments in new technology to support the program, may have contributed to increasing administrative costs. There is other evidence of efforts to improve the efficiency of the program through, for instance, a Lean review of the call for proposals process and use of electronic methods for the application process and review and tracking of projects. Also notable, WP funds are leveraged by funded organizations in the order of one-third to one-half of the total project cost. Within the resources that are available, the program is purposeful about collecting lessons learned from its calls for proposals and from projects for program improvement and determining emerging issues.

Recommendations

- The program should continue to fund projects with a view to fostering systemic change. Key elements that were found in the evaluation to have the potential to support and increase systemic change include:

- continue to embed and clarify expectations for sustainability of project impacts and systemic change within calls for proposals;

- embrace new flexibility to fund advocacy activities to complement the multi-component approaches that are currently being used by many projects to influence policy and institutional change; and

- explore opportunities to fund longer-term, higher value projects with multiple components to foster longer-term impact.

- Increase efforts in knowledge translation/dissemination at the program level.

- Enhance capacity across the program to support funding recipients through the project lifecycle to optimize their approach and efforts to achieve sustainable and systemic change.

1.0 Purpose

This document presents the findings and recommendations from the 2016–17 evaluation of Status of Women Canada’s Women’s Program. The evaluation was designed to provide comprehensive and reliable evidence to support decisions regarding continued delivery of the program.

The report is structured as follows:

- Section 2.0 presents a description of the WP;

- Section 3.0 presents the objectives, scope and methodology of the evaluation;

- Section 4.0 presents findings related to the issue of relevance, design and delivery, and performance; and

- Section 5.0 presents the conclusions and recommendations.

2.0 Program Description

2.1 Program Context

Status of Women Canada (SWC) is a federal government agency that works to advance equality for women and to remove barriers to their participation in society; it promotes the full participation of women in the economic, social and democratic life of Canada. Created in 1973 in response to a recommendation of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, the Women's Program (WP) has been housed within SWC since the mid-90s. This grants and contributions (Gs & Cs) program provides funding to Canadian organizations to support community-based projects that work to advance equality for women in Canada by creating conditions for success for women. Funded projects occur at the national, regional, and local levels and work to address three priority areas: ending violence against women; increasing women’s economic security and prosperity; and encouraging women’s leadership and democratic participation.

2.2 Program Profile

Two main funding mechanisms are available to organizations under the WP:Footnote 1

- Grants (approximately 80% of the current funding) are provided to organizations based on a relatively low level of assessed risk;Footnote 2

- Contributions (approximately 20%) are used for projects presenting high materiality and level of risk.

Applications for funding to the WP are received through various types of calls for proposals: open; targeted (focusing on specific issues and themes); and invitational. A small number of applications to the WP are also received through a continuous intake (CI) process. Applications are received using an online automated system, which also includes an assessment tool for reviewers. During the period under study, 10 calls for proposals were issued.Footnote 3

Eligible recipients identified as part of the renewed WP Terms and Conditions (Ts & Cs) effective 2013, include legally constituted organizations that are: not-for-profit Canadian organizations, excluding labour unions; for-profit Canadian organizations; Indigenous governments (including band councils, tribal councils and self-government entities) and their agencies in rural and remote areas; Territorial governments (local, regional, Territorial) and their agencies in the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut; secondary schools and school boards.

All projects are required to demonstrate that they contribute to the WP outcomes. Specifically, funding is provided for activities that: contribute to addressing the WP’s mandate and objective; fall within one or more of its areas of focus; articulate clear plans to achieve demonstrable outcomes; involve women who are affected by the issue; and support the activities of regional or national networks and centres of expertise advancing a priority in strategic partnership with others. Leveraging of funding from other sources is encouraged, but not mandatory.

Projects are diverse in nature and scope; target different beneficiaries; and apply a variety of strategies to address various issues. Funding is provided for a maximum of 36 months, and the maximum is $1.5 million over three years. During the period under study (2011–12 to 2014–15), 402 new projects were funded with an average value of about $240K.

In addition to Gs & Cs funding, the WP provides technical assistance (e.g., ongoing support, oversight) to women's groups and other equality-seeking organizations. As well, the program contributes to SWC’s knowledge management and dissemination activities. In 2013–14, the WP started organizing knowledge exchange sessions for funded projects, allowing funded recipients and other stakeholders to share their knowledge and expertise, in particular for practical problem-solving on implementation issues.

2.3 Structure and Governance

Overall accountability for program implementation resides with the SWC Coordinator/Head of Agency. Reporting to the SWC Coordinator, the Senior Director General of the Women's Program and Regional Operations Directorate is responsible for the delivery, performance and accountability of the program. Delivery of the WP is decentralized via a national office and three regional offices: Atlantic; Quebec;Footnote 4 West/Northwest Territories/Yukon and Ontario (co-located with the National office). The National office is located in the National Capital Region and also serves Nunavut.

Project proposals that are local, regional or provincial/territorial in nature are assessed for eligibility by the regional offices. Proposals that are national in scope or that focus on Indigenous communities are assessed by the national office. Funding recommendations are provided by the national and regional offices based on criteria outlined in the project assessment guidelines. Funding decisions consider program priorities, alignment with targeted calls, areas of demonstrable need, potential for substantial impact and linkages with government-wide priorities as well as risks. Final approval of applications rests with the Minister of Status of Women Canada.

2.4 Resources

The WP is a permanent program; the Ts & Cs that are the focus of this evaluation came into effect in 2010–2011 and were modified in September 2012. The Gs & Cs funding envelope for the years 2011–2012 to 2014–2015 was $19.03 million per fiscal year. In 2015–2016 and ongoing, the envelope is $19.48M, reflecting additional funding under the five-year Action Plan to Address Family Violence and Violent Crimes against Aboriginal Women and Girls, as well as the Action Plan for Women Entrepreneurs. These two initiatives were outside the scope of the current evaluation. The program’s financial data for the years 2011–2012 through 2014–2015 are presented below (Table 1). Overall, the program had a budget of $89.6M over the four years under study.

| 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTEs | 32 | 35 | 34 | 39 | n.a. |

| Salary | $2,923,415 | $2,810,403 | $2,849,319 | $3,015,766 | $11,598,902 |

| O & M | $351,757 | $768,351 | $867,939 | $734,184 | $2,722,231 |

| Gs & Cs | $18,285,051 | $18,887,046 | $19,033,333 | $19,033,332 | $75,238,762 |

| Total | $21,560,223 | $22,465,800 | $22,750,591 | $22,783,282 | $89,559,896 |

2.5 The Program’s Theory of Change

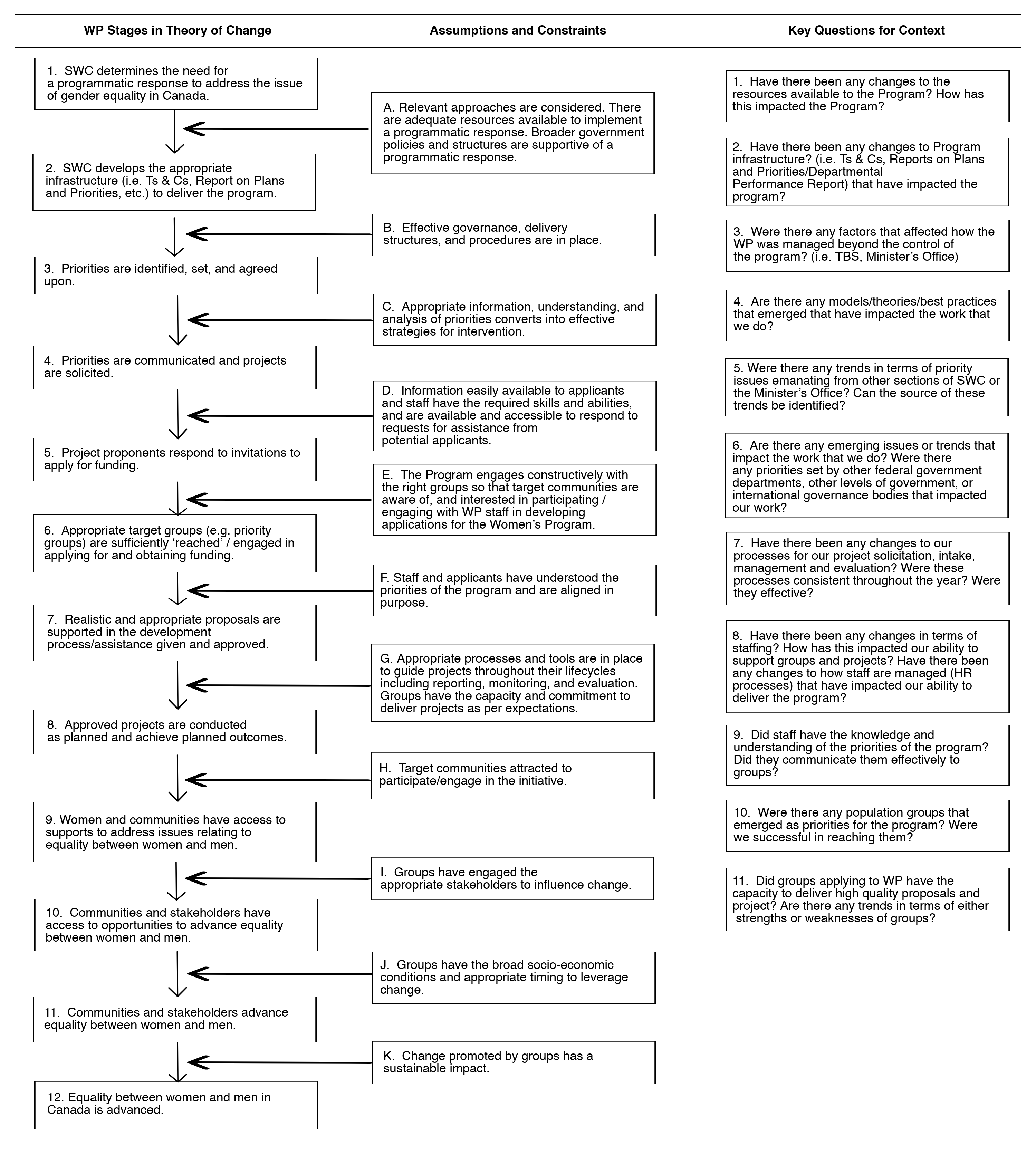

The WP detailed results chain (see Annex A) demonstrates a continuum where project activities and outputs lead to achieving immediate level outcomes (access to supports), which in turn will lead to intermediate level (increase/strengthen access to opportunities) and longer term (work to advance equality between women and men) outcomes.

The immediate outcome, “Women and communities have access to supports to address issues relating to equality between women and men”

refers to the resources, tools, networks, etc. available to women and communities. The intermediate outcome is “Communities and stakeholders have access to opportunities to advance equality between women and men”

. These outcomes are expected to lead to the program’s longer-term outcome “Communities and stakeholders advance equality between women and men”

with an indicator of evidence of action (e.g., use/application of supports/opportunities, sustainability of partnerships). Taken together, these three outcomes are then expected to contribute to the WP’s ultimate outcome: “Equality between men and women in Canada is advanced.”

The inclusion of communities at each of the outcome levels reflects the goal of the program to foster systemic (versus individual) change that is associated with more durable project impacts and improved value for money of public resources. The program’s theory of change sets forth not only the continuum of expected results but also their related implementation assumptions, constraints, and limitations at various stages. The inclusion of an implementation component in the theory of change ensures that contextual factors affecting program delivery and performance are taken into consideration in assessing the program’s outcomes.

3.0 Evaluation Description

3.1 Objectives and Scope

The evaluation objective is to provide management with credible and reliable evidence to inform SWC decision-making about the WP’s future directions. The evaluation considers all activities and intended outcomes as articulated in the program’s theory of change since the previous evaluation of the WP (2007 to 2011). It uses multiple lines of evidence to describe to what extent and how the WP has achieved its intended impacts.

A theory-based approach to the evaluation was used to understand the complexity associated with the delivery and achievement of WP outcomes. This type of analysis is particularly relevant to the WP evaluation given the number of factors associated with achieving the goal (gender equality), the duration of projects (a maximum of 3 years), the funding permissible ($1.5 million), the need to engage and influence the actions of multiple stakeholders, and the difficulty of measuring each of these elements independently, and in their relationship to one another.

3.2 Issues and Questions

The evaluation addresses issues of relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the WP through seven key questions. The evaluation questions, related indicators, and data sources are presented in Appendix B.

3.3 Evaluation DesignFootnote 5

To ensure a valid assessment of the program, the evaluation uses multiple lines of evidence, including both qualitative and quantitative methods, and gathers data from various perspectives (e.g., program management and staff, partners, funding recipients, external experts).

Document Review: A review of program, corporate and government documents was conducted to assess the relevance and performance of the WP. SWC provided most program documents which included the Terms and Conditions and annual reports, as well as materials related to the calls for proposals such as applications, guidelines and assessment tools. Corporate and government documents included materials such as Agency performance reporting and federal budgets, Speeches from the Throne and the Ministerial mandate letter. Documentary sources were useful to assess program alignment with federal government and Agency priorities and strategic outcomes and understand the key assumptions and constraints identified in the program’s theory of change.

Literature Review: An analysis of peer-reviewed and grey literature was conducted to provide evidence for the relevance of the WP, in particular, the ongoing need for the program. The focus of the search was on reports published in the last five years related to various indicators of gender inequality specifically pertaining to the three program pillars. Various search engines (i.e., Scholar’s Portal, PubMed, Academic Search Complete) were used to identify academic literature and grey literature (Google/Google Scholar). The literature review was complemented by a comparative analysis with other funding programs in Canada, and in other jurisdictions with objectives similar to the WP.

Administrative Data Review: The administrative data review provided quantitative information including the number and characteristics of projects that were funded during the period under study. Financial data related to the delivery of the WP, including allocated and actual expenditures were also examined to contribute to addressing questions of efficiency and economy.

File Review: A sample of 31 project files representing about eight per cent of all projects funded during the study period were reviewed using a structured template based on the evaluation questions and indicators. Materials such as the project proposal/contribution agreement, needs assessment/gender-based analysis (GBA), partnership template, project final report, and project evaluation report, if available, were examined.

Interviews with Key Informants: Interviews with 21 key informants were conducted to gather in-depth information with respect to all evaluation issues and questions. Key informants were selected based on their knowledge of the WP or familiarity with gender equality issues in Canada overall. Respondents included staff from headquarters and the regions (n=5), partner organizations (other federal, provincial government and non-government organizations (NGO) representatives (n=12), and experts (n=4).Footnote 6

Survey of Applicants: A bilingual online survey was conducted to obtain perceptions and views from representatives of applicants on their satisfaction with the WP as well as the impacts and sustainability of WP funded projects. A total of 190 funded organizations, and 103 non-funded organizations completed the survey for a response rate of 65% for funded organizations and 29% for non-funded organizations.

Case studies: Three case studies were conducted of selected clusters of projects funded by the WP, including projects that focused on campus violence, women in technology, and projects that received successive funding over two time periods. The intended purpose of these case studies was to examine the impacts of these clusters of projects on systemic change, their sustainability, and where possible, their economic impacts and key factors driving change. Case studies involved a review of documentation as well as interviews with project stakeholders (e.g., project lead, partners, participants).

3.4 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Most evaluations encounter limitations that may have implications for the validity and reliability of their findings and conclusions. Some of the key challenges and limitations of this evaluation include:

- Measuring achievement of outcomes and attributing these outcomes to the WP. While there is evidence that organizations’ projects are supporting some types of systemic change (e.g., changes at the institutional or policy level) there is a lack of precision in terms of quantifying the magnitude or significance of these changes for individual projects and for the program overall. As well, achievement of systemic change and advancing gender equality are longer-term program goals that are difficult to measure, and to detect in a five year period. They are also likely to be influenced by other factors in the broader environment such as policy change;

- The diversity of funded projects (types of interventions, outputs, target groups and outcomes) created challenges to aggregate findings, particularly for telling the WP’s overall performance story in terms of the program’s intermediate and long-term outcomes;

- The evaluation considered multiple ways to include diversity at the planning phase. Efforts were made to include an intersectional lens in the data collection instruments to support some intersectional analysis and reporting in later evaluation phases. This however, does not represent a truly intersectional approach as program beneficiaries were not included in the different phases of the evaluation. While this has not necessarily posed a challenge for the evaluators in carrying out the study, it is potentially problematic that principles driving the women’s movement were not fully incorporated into an assessment of a program supporting it;

- The evaluation took place during a change of government. During the evaluation, the priorities and direction of the new government had a substantial impact on SWC as a whole, including the WP’s funding and scope of operations. This may have influenced key informants’ views, for example.

3.5 Considerations on Including Intersectionality as a Way to Incorporate Gender in Evaluation

Where possible in this evaluation, intersectional analysis was included as a consideration in the methodological approach. For instance, primary data collection during the evaluation (e.g., key informant interviews, survey of funding recipients) examined intersectionality to the extent possible. However, the program does not intentionally integrate intersectionality into its program design and delivery; consequently, related comprehensive historical program performance data was unavailable. The evaluation would have benefited from a more robust evidence-base in this area.

4.0 Findings

4.1 Relevance

Ongoing need for the Program

Trends/statistics related to gender equality

The World Economic Forum Gender Gap index is a common measure of national gender equality. Since 2006, Canada's overall ranking across the four sub-indexes (which include economic, educational, health-based and political indicators) has remained stable at between 18th and 21st position. In 2016, Canada slipped to a ranking of 35th of 144 countries and closed 73% of its overall gender gap (as measured by four sub-indices of economic participation and opportunity, political empowerment, educational attainment and health and survival).Footnote 7 Evidence of progress toward gender equality is clear in education and labour force participation: the percentage of women with a post-secondary degree or diploma has more than doubled between 1991 and 2015 (from 29 to 61%) (growing at a much faster rate than men)Footnote 8 and women’s participation in the labour force is currently at an all-time high, corresponding to 47% of the workforce in 2014.Footnote 9 Other data, however, indicate that there remain significant inequalities between women and men in critical areas (Table 2).

| Pillar | Selected evidence |

|---|---|

| Violence |

|

| Economic prosperity |

|

| Leadership |

|

It should also be noted that the literature and data indicate significant disparities between sub-groups of women in terms of equality measures. For instance, Indigenous women are eight times more likely to be killed by their intimate partner, nearly three times more likely to report being a victim of violent crime and have a national homicide rate seven times higher than non-Indigenous women. Indigenous women, as well as women with disabilities, and seniors who are single are more likely to experience poverty.

Key informants agreed that the needs addressed by the WP remain strong. While a few interviewees felt that progress on women’s leadership has advanced over the timeframe of the evaluation, progress towards ending violence against women and increasing women’s economic security are viewed as having stagnated in the period under evaluation.

Continued relevance of the three pillars

The evidence confirms that the WP’s three pillars continue to be relevant and reflect areas where significant gender disparities continue to exist (see Table 2). Internationally, programs with similar objectives organize their funding in a comparable way. The cross-jurisdictional review identified several funding programs that have similar priorities to the WP such as those in Australia (i.e., the Women’s Leadership and Development Strategy, which provides grants through the Office of Women), Ireland (i.e. Equality for Women Measure, which provides grants funded by the European Social Funds (ESF)), and the regional approach of the Nordic Council of Ministers for Gender Equality (i.e. Nordic Council of Ministers Funding Scheme for Gender Equality, which funds projects that dually support Nordic cooperation).

Several mechanisms are in place to ensure the program’s strategic priorities are aligned with areas of need. For instance, SWC regularly reviews trends, areas of interest and evolving issues, and the changing needs of women in Canada to identify strategic priorities for funding. Further, a review is conducted prior to each call for proposals to confirm the relevance of the issues and need for programming. The program also conducts periodic literature reviews and analyzes previous calls (both successful and unsuccessful proposals) to synthesize the types of needs being reported by applicants.

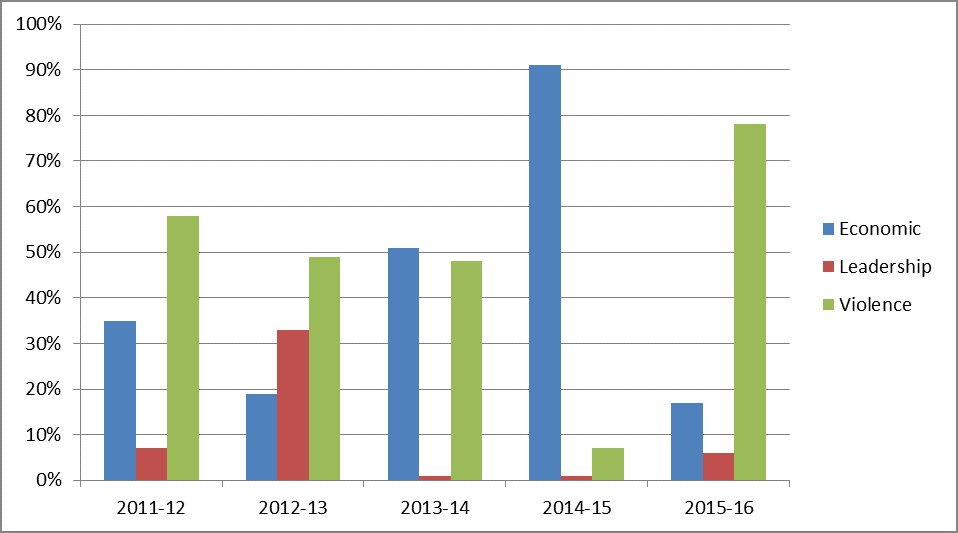

There has been a high degree of variation during the period under study in terms of the percentage of projects funded under each pillar. For instance, the proportion of projects funded annually under the economic pillar has ranged from 19% in 2012–13 to 91% in 2014–15 when the program became more involved in previously less well developed areas, such as entrepreneurship and women in the skilled trades. Consistently fewer projects have been funded under the leadership pillar (ranging from 1 to 7% each year, with the exception of 2012–13 when 33% of projects were related to leadership).

Text version of Figure 1: Projects Funded by Year and Pillar (Percent)

| 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | 35% | 19% | 51% | 91% | 17% |

| Leadership | 7% | 33% | 1% | 1% | 6% |

| Violence | 58% | 49% | 48% | 7% | 78% |

Key informants considered the current three pillars to be relevant, if broad. Suggestions (from external interviewees) for new pillars that the WP might develop include girls and Indigenous women (both areas in which the program has already made contributions).

Program demand and need

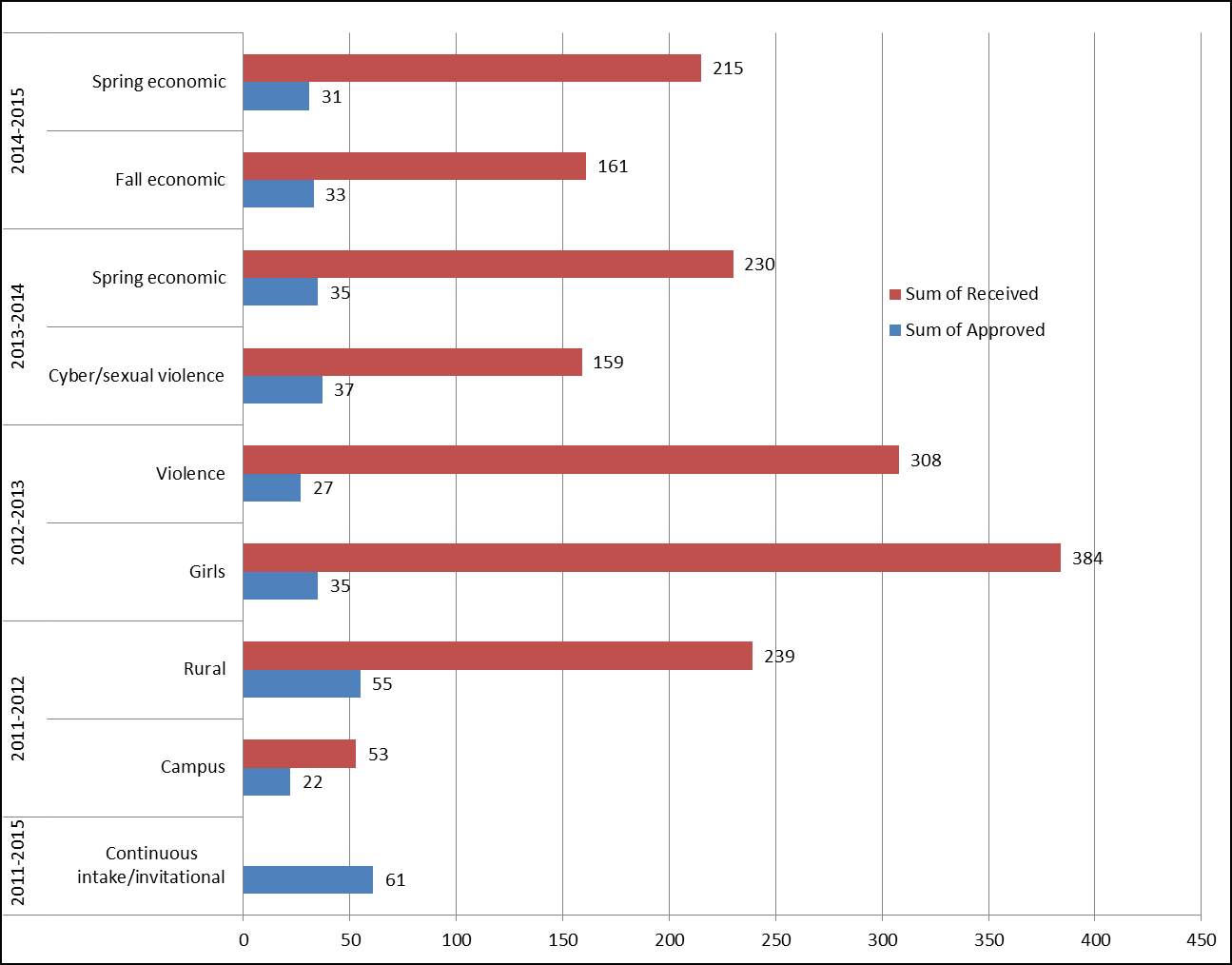

Requests for program funding have been strong across the various calls. The success rate of applications was 16% (on average) between 2011–12 and 2014–15 (excluding invitational and CI applications as the same assessment criteria don’t apply).This is even lower than the previous evaluation period which was 26%.

This figure fluctuates greatly depending on the call; from a low of 9% for open calls to a high of 42% for more targeted types of calls. The ability of organizations to complete their projects appears high as very few projects are terminated prior to their completion (3/402 funded projects during the period under study).

Text version of Figure 2: Applications Received & Approved, by Call and Year

| Fiscal year | Calls for proposals | Number of applications received | Number of applications approved |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2015 | Spring economic | 215 | 31 |

| Fall economic | 161 | 33 | |

| 2013–2014 | Spring economic | 230 | 35 |

| Cyber/sexual violence | 159 | 37 | |

| 2012–2013 | Violence | 308 | 27 |

| Girls | 384 | 35 | |

| 2011–2012 | Rural | 239 | 55 |

| Campus | 53 | 22 | |

| 2011–2015 | Continuous intake/invitational | n/a | 61 |

Consistency of the Program with SWC strategic outcomes

The SWC strategic outcome is: “Equality between women and men is promoted and advanced in Canada”

. The WP falls under Program 1.2: Advancing Equality for Women. Departmental performance reporting during the period under study points to the WP as supporting the Agency's strategic outcome by providing Gs & Cs funding to Canadian organizations to support action by carrying out projects that will lead to gender equality across Canada. The three pillars of the WP are aligned to three of the five SWC organizational priorities which are: addressing violence against women and girls; increasing representation of women in leadership and decision-making roles; and promoting economic opportunities for women.Footnote 21

Consistency of the Program with federal priorities and role and responsibilities

Correspondence between WP and federal priorities

The documentation indicates that there is a high degree of correspondence between the mandate, objectives and priorities of the WP, and past and current federal government priorities. In previous years, the program was observed to align with federal priorities related to economic prosperity and funding priorities for the program reflected this focus. During 2014 and 2015, for instance, the federal Economic Action Plan pledged support for women entrepreneurs and to increase women’s participation in corporate leadership. During the period under study, about 40% of projects were funded under the economic pillar, including calls for proposals in areas such as entrepreneurship and women in skilled trades and professional occupations. Program calls for proposals within the violence pillar also aligned with Ministerial and government-wide priorities at the time. For example, the choice of a trafficking theme under the violence call was related to the establishment of the National Action Plan on Trafficking, and a call theme related to violence in the name of “honour”

responded to a Speech from the Throne commitment to address this issue.

The program also aligns with the priorities of the new government. While the current government's mandate letter to the Minister of Status of Women does not specifically mention the WP, the 2016 Budget increased capacity of the program by allocating $23M to SWC to, in part, expand the Agency’s regional presence across Canada to support local organizations working on women’s issues and gender equality.

Correspondence between WP and federal roles and responsibilities

The WP supports Canada's ability to achieve its domestic and international commitments related to gender equality. Domestically, the program supports the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms – Section 15 – Equality Rights that enshrines equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination, including on the basis of gender. With respect to its international obligations, Canada ratified the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women in 1981, as well as the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (Beijing) resulting from the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995. As a signatory, Canada commits to achievement of equality between men and women, regardless of their marital status, in all aspects of political, economic, social and cultural life.

The WP is also consistent with efforts of national governments in other industrialized countries to address inequality between women and men. The majority of the G20 countries are currently making improvements to policies to promote gender equality. Many countries and multilateral organizations have gender equality strategies and/or strategies to address violence against women. (e.g., The Council of Europe Gender Equality Strategy (2014–2017), National Women's Strategy 2007–2016 (Ireland), The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (Australia)).

Overlap and duplication

In general, the evaluation found little evidence of duplication between the WP and other funding sources. SWC is the only federal organization working explicitly to advance gender equality through systemic change. Some other provincial organizations (provincial and territorial Women’s Directorates or Offices) and non-profit entities (such as the Canadian Women’s Foundation) provide some funding to support similar objectives to the WP, although it was noted by key informants that these grants are typically smaller, and regional in scope. Key informants viewed these other funding sources as being largely complementary to the WP, and the need was perceived to exceed available funding from all sources.

Some key informants noted that while intersectional approaches are increasingly recognized as important, inherent tensions are present when working on cross-cutting issues and/or with groups of women expressing multiple intersections of identity. Key informants noted that each of these diverse groups of women have an affiliated department with a mandate responsible for that group. The WP does not want to unintentionally disown the role of these departments in undertaking gender-sensitive work. Focusing on the multiple barriers faced by Indigenous women, for example, may duplicate work within the mandate area of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. At the same time, interviewees articulated the growing importance and need for intersectional approaches overall.

The survey findings confirm that WP funding is very important for applicants. Over 80% of funding recipients say their project would not have proceeded without WP funding, and among unfunded applicants, almost one in six indicated their project did not proceed because they were not funded by the WP. Among those whose projects did proceed, activities or participants were reduced. Typical external sources of funding (aside from organizations’ own resources or volunteers) were from the private sector; provincial government; and non-profit or community-based organizations.

4.2 Design and Delivery

Key Findings:

Profile of funded applicants: The WP funded over 300 organizations across all regions during the period under study. Organizations are drawn from various sectors, including both women’s groups and mainstream organizations. The program is proactive in its efforts to solicit quality proposals and applicants are generally satisfied with the availability of information about the program. Some challenges identified included meeting the program’s partnership requirement and fostering systemic change.

Design and delivery features: Analysis indicates that there is a logical link between the WP and achievement of immediate and intermediate outcomes. The evaluation confirmed many of the underlying assumptions about delivery in the program’s theory of change (e.g., adequate resources, effective delivery mechanisms, appropriate identification of priorities), although program applicants and key informants identified some areas for improvement (e.g., more clarity with respect to the application guidance and assessment criteria, streamlining the application, and strengthening feedback to organizations when projects are not funded). Key informants also noted a few areas of program capacity requiring improvement, including enhancing capacity for knowledge sharing, increased engagement with partners, and addressing regional-Headquarters consistency in managing calls.

Profile of funded applicants

The WP funded 402 projects with 326 organizations during the period of study. The WP undertakes a variety of promotional strategies to cultivate interest in the program. Most applicants (69%) were satisfied with the availability of information about the funding opportunity. During the study period, there was a priority to expand the scope of the types of organizations funded by the program. Program key informants noted that many new groups serving women entrepreneurs, sector councils, and organizations working with women in skilled trades were funded as a result of the calls under the economic pillar. The survey data confirm that funded applicants include both women’s organizations (47%), as well as mainstream organizations that are identity- or issue-focused, or a combination (53%). According to the WP's annual report, outreach to Indigenous organizations was a priority during the study period and was reportedly successful through targeted promotion of the WP (information sessions, networking with other provincial and federal departments, regional travel), additional technical assistance and flexibility in assessment.

Some eligibility criteria (e.g., restrictions on funding advocacy and research projects) were seen by key informants to be overly restrictive and limiting the program’s ability to achieve its objectives. Furthermore, both internal and external key informants referred to the challenge presented by requiring organizations to partner (and especially the most recent call which requires organizations to co-apply). While they felt the rationale for this was sound, they also noted that it makes it difficult for smaller organizations to access WP funding.

Program design/delivery features

Calls for proposals. In addition to using a variety of methods to solicit proposals (e.g., “open”

calls, targeted calls, etc.), the WP developed specific guidelines corresponding to the type of call (e.g., timelines available, topic area, and applicant pool). The mix of open and targeted calls was viewed by key informants as effective overall. In general, applicants were pleased with the relevance of the selected themes and priority areas. However, some key informants also identified that targeted calls over-focussed on some issues and organizations at the expense of others, possibly leading to mission drift of the community organizations and causing some tension and controversy among partners. Further, some interviewees perceived that this resulted in funding weaker projects. In a few cases, funding decisions were also felt to be politically driven, causing discord amongst different organizations working within the women’s movement.

Application process. Satisfaction with the program application process among surveyed applicants is somewhat mixed; seven in ten funding recipients are satisfied with the WP application overall compared to 28% of unfunded applicants. In general, applicants were satisfied with the support provided by the program staff. Similar to the previous evaluation, lower levels of satisfaction among both funding recipients and unfunded applicants were expressed with the amount of time available to prepare an application, the complexity of the application (e.g., financial/budgeting information required), timeliness of learning the result of their application and a lack of clarity with respect to application guidelines and assessment criteria. Unfunded applicants desired more information about why their application was not funded – half of unfunded applicants said they did not know why they did not receive funding.

Program capacity. A small number of applicants (one in ten) noted challenges with lack of access to support from program staff or lack of consistent messages during the application process. Better communication between the regions and with headquarters on managing calls was noted as a potential program improvement by several internal key informants.

4.3 Achievement of Intended Outcomes

Key Findings: The WP is achieving its intended immediate outcome of creating supports to address issues relating to gender equality. Most funded projects lead to the development of tools and/or other types of supports in each of the three pillars, far exceeding the program’s target. These products are diverse, and some reflect an intersectional approach by addressing multiple dimensions of inequality. Ensuring that communities and stakeholders have access to opportunities to use or apply the tools and supports – the program’s intermediate outcomes – is being partially achieved by dissemination and promotion of tools and supports. This occurs electronically through website or social media channels. However, as noted above, the evaluation suggests additional investments in knowledge sharing by the program would further support achievement of this intended outcome.

Partnerships at the project level are key to transferring project products and sustaining their diffusion during the project and at the end of funding. Reflecting program criteria, funded projects consistently engage a large and diverse number of partners during the project. Funding recipients expect partnerships to continue beyond the project.

Sustainability of the projects’ impacts to achieve the program’s longer-term outcome – communities and stakeholders advance equality between women and men – does not occur in all or even most projects. While most closed projects indicate that impacts are being sustained in some manner, this is largely through passive methods such as maintaining access to products on their website, or assuming that individuals who have been trained/mentored will adopt and even promote project learnings. While it is difficult to measure the magnitude or significance of the impact, between one-third and four in ten organizations indicate that their project has achieved sustainability after WP funding ended through policy, practice or institutional change, or that changes to programs or policies as a result of their project are advancing gender equality.

Program capacity to achieve the program’s goal of systemic change was questioned by some. Internal and external stakeholders feel the program’s exclusion of advocacy and research as eligible activities compromises the ability of the program to achieve desired systemic change. Having the option for longer time-frame agreements was also recommended to increase projects’ potential to achieve systemic change.

Immediate Outcomes

Development of tools and supports

The WP’s immediate outcome “Women and communities have access to supports to address issues relating to equality between women and men”

refers to the resources, tools, networks, etc. available to women and communities. The majority of projects include the development of tools (73%) and/or supports (78%) as a key component of their project. This is more than the program’s target of 50%. Almost all projects include activities to foster awareness/engagement around these tools and supports (93%).

The review of project files showed that most WP projects developed a wide array of tools and supports, and many were tailored to their target group(s)’s experience of inequality. Examples of tools identified in the file review and survey of funding recipients included: e-learning modules, curriculum, webinars and training programs; toolbox/toolkits on subjects such as GBA; promising practices manuals on subjects such as response to sexual assault/disclosures of sexual assault, connecting women to meaningful employment, women's leadership training; Action Plans or guides on subjects such as recruiting and retaining women in the trades; service protocols such as for frontline workers working with specific target groups to respond to gender-based violence; posters/brochures/pamphlets/website on topics such as marriage and rights, cyber sexual violence; Community Action Plans (and associated work books and tool kits); and needs assessment/audits/resource inventories/service mapping.

In terms of supports, projects have included: creation of local, regional and national networks of organizations to address issues such as ending violence; development of individual-level supports including support groups, mentorship relationships, drop-in programs and training/workshops; and the creation of formal structures such as advisory committees, and Memorandums of Understanding between partner organizations to address issues such as cyber violence and campus violence.

In addition to development of tools and supports, other common components of WP-funded projects include: interventions with individual women participants (76%); community-level activities (76%); and, to a lesser extent, interventions with service providers (68%). The number of project components is a key predictor of achieving sustainable or systemic change (that is; projects with multiple components are more likely to indicate impacts at the level of operations, policy or practice).

Intermediate Outcome

Facilitating opportunities

The WP’s intermediate outcome is about facilitating opportunities for communities and stakeholders to access, use or apply tools and supports. Communities and stakeholders’ work to advance gender equality is achieved through promotion and dissemination of the project tools, protocols or models to broader groups of stakeholders.

Tools and supports developed by projects are disseminated through multiple channels, with a focus on electronic dissemination via website (65%) and through social media (59%). Most organizations are directing their efforts to multiple audiences. The most common key audience(s) for the tools and/or supports created were: individual women/girls (85%) and organizations or groups (such as companies, NGOs) (80%), followed by communities (59%) or networks (e.g., associations or umbrella organizations (56%), and less commonly, a sector (42%).

Partnerships

In addition to the dissemination of tools and supports, a key vehicle for projects to facilitate opportunities is through establishing partnerships. WP calls for proposals during the study period consistently emphasized this requirement in the application assessment criteria to address the complexity associated with achieving systemic change. Accompanying applicant guidance insists on engagement of key stakeholders which are defined specifically for the context of the call (e.g., businesses, youth groups, women's and community organizations, legal institutions and law enforcement agencies, local, regional and provincial governments, sector and professional organizations or communities). The expectation is that stakeholders will also contribute to identification of priorities, systemic barriers, and promising opportunities to address the specific needs of women. Funding recipients most commonly partnered with community-based/non-profit organizations (89%). This was followed by universities or colleges (56%), a provincial government department/agency (42%), company or industry association (40%), municipal government (37%), school (32%), police (31%) and Indigenous organization/government (26%).

Surveyed funding recipients confirm that partnerships are important to the achievement of objectives; with partners being involved in the design of the project, but more commonly during project implementation. On average, projects involved 11 partners. Over three-quarters of projects engaged new partners for their projects and partners were highly diverse, representing many sectors and types of organizations. The types of partners engaged mirrors recipients’ responses in 2012, with the exception of more significant engagement of the private sector during the current period under study. Partners were more likely to be engaged in project implementation rather than in project design. In some instances, funding recipients noted historical relationships with partners; 76% of funding recipients noted some prior working relationships. Funding recipients noted that the key benefits of partnerships included contributions of advice/expertise and awareness/promotion of the tools and supports developed by projects. Further, over three-quarters of funding recipients (77%) indicated that partners had helped achieve results beyond what their organization could have achieved alone.

Funding recipients report significant longevity of their partnerships following the completion of the project. Among surveyed funding recipients whose project has finished, 91% say that project partners continue to be part of the organization's network after funding is complete, 82% say that partnerships benefit other activities or projects in their organization, and 75% say that project partners are working together again. Projects that have multiple components were more likely to indicate these impacts.

Longer-term Outcome

The program’s longer-term outcome – communities and stakeholders advance equality between women and men (as indicated by evidence of sustained use/application of supports/opportunities) – is achieved to some degree. Most completed projects (90%) have some form of sustainability following the funding period, though two-thirds of projects continue on a limited scale (67%) or for a limited period of time (12%). Only rarely do organizations indicate no ongoing impact of their project after the funding period. One-half of funded projects indicate that the sustainability of their project is being achieved due to one of two reasons: first, because individuals who have been trained or mentored will continue to apply their skills/knowledge beyond the project; or, sustainability is being achieved through the advancement of community plans. Somewhat fewer (42%) projects indicate that models/resources have been transferred/are being used in other settings.

While it is difficult to quantify the magnitude or importance of the change, between one-third and four in ten closed projects indicate sustainability of their project through some kind of change to operations, policy or practice. For instance, about four in ten closed projects that say their project was sustained after WP funding ended, achieved this through a change in operations, policy or practice of their own organization or their partners. Just over one-third (36%) of closed projects say that policy or program changes resulting from the implementation of project tools and/or supports are leading to actions to advance gender equality. As mentioned above, project with multiple components were more likely to indicate these types of impacts.

The evaluation gathered many examples of sustainable change from the case studies which included, for example, development or enhancement of sexual assault policies and creation or enhancement of new positions dedicated to providing services or advocacy pertaining to sexual assault within post-secondary institutions. Under the economic pillar, the Women in Technology initiative made progress both in terms of mentorship of individual women in the information, communications and technology (ICT) sector, as well as working at the level of the sector and companies. The case study of this initiative found increased attention to gender equality in the sector’s policy agenda and evidence of modifications to institutional HR practices, including evidence of impacts on a company pay structure and policies to ensure equal pay between women and men. Lastly, the case study on successively funded organizations discussed the effect of “longitudinal momentum”

resulting from a second round of funding: this refers to when the success of the first project allows for more ambitious targets and impact in the second. In one project example from that case study, the involvement of a larger number of stakeholders in the second project led to the eventual development of a sector-wide action plan.

While acknowledging these impacts, it should be noted that internal and external key informants raised questions about the current design and capacity of the WP to achieve systemic change. Specifically, many felt strongly that the exclusion of advocacy and research from eligibility for funding hampered the program’s potential to achieve systemic change.Footnote 22 For the same reason, many internal and external key informants favored increased flexibility for the program to establish longer funding agreements (i.e., five years) and higher maximum funding amounts. As noted above, the case study on successively funded organizations demonstrated that multiple funding opportunities provide the opportunity to increase the reach, impact and sustainability of initiatives. Internal and external key informants also suggested that the WP play a role in knowledge sharing, by disseminating project outcomes and engaging in community of practice work. Finally, program partners in the government and community sector would like to see a more robust and strategic partnership with the program, including greater information sharing.

Contextual Factors

Key Finding: From the perspective of the program, contextual factors that facilitate project success include a strong GBA and needs assessment that provide a foundation to tailor the intervention to local needs, as well as adequate planning and support for sustainability. For funding recipients, key facilitating factors for their project included the strength and capacity of their organization, interest of the community/target group and the engagement of partners. Common challenges that projects experience are the complexity of the systemic barriers they are trying to address and institutional resistance to change.

Intersectionality has increased in importance, both for the WP and its stakeholders. While a GBA+ approach does pose challenges for how the program is positioned in comparison to other federal partners, the organizations funded by the WP view the ability to account for multiple barriers as a key factor in facilitating project success.

Program documentation evidence included internal analyses conducted to identify factors that facilitate or hinder the success of projects in order to support program improvement and project success. In terms of facilitating factors, the quality of the project’s GBA and needs assessment was often noted as a factor contributing to success. A strong process allows organizations to better understand the systemic barriers affecting the target population, industry or sector and to adapt their projects to specific contexts. Program Annual Reports and internal analyses of various calls for proposals identify difficulty in understanding and planning for sustainability as a key barrier impacting project success (e.g., need to support projects to work with partners to embed or institutionalize tools, resources or models that had been developed by the project).

According to surveyed funding recipients, factors that commonly facilitated implementation have to do with the proponent organization itself (capacity and reputation, strengths of staff), interest of the community and women in the project, engagement of appropriate and diverse partners, and the amount of WP fundingFootnote 23. Guidance and support from SWC during implementation received a modest rating; only about half of funding recipients indicated that this was a facilitating factor of project success. Factors that inhibit project success or challenges experienced during implementation often have to do with the complexity of the issues/barriers that are being addressed and, for some, institutional resistance to change. While partnerships are identified as an important facilitating factor, partnerships also come with challenges including the time it takes to engage and sustain partnerships.

Intersectionality

The evaluation gathered evidence regarding intersectional approaches and the extent to which they occurred within the projects the WP funds and facilitated project success. In general, while intersectionality is evident within the program’s activities, this approach presents some challenges with respect to SWC’s role vis-à-vis other departments working with the same target groups.

Internal stakeholders discussed the challenge that championing intersectional approaches poses for the WP in key informant interviews. Namely, they noted that each group of marginalized women has a department with a mandate responsible for that group, and the program does not want to encroach on the role of these departments in undertaking gender-sensitive work. However, they also stressed the ways in which the program has tried to incorporate some work on doubly disadvantaged groups, for example, through themes within calls.

Program partners articulated the growing importance, and need for intersectional approaches, and perceived intersectionality to be an emerging thread of the program. Furthermore, SWC’s own documentation (such as the Departmental Performance Reports) asserts that the increasing use of intersectional analysis is raising service providers’ awareness of the importance of developing coordinated approaches to respond to the multiple barriers facing many women, particularly under the pillar of violence.

Funding recipients were asked about intersectionality, and specifically, to what extent understanding intersecting barriers to equality may have inhibited their project’s success, or alternatively, may have facilitated it. More than two thirds thought that the consideration of other identity factors such as income, ethno-cultural grouping, and geographic barriers actually facilitated the implementation of their project.

Unintended Outcomes

WP funded projects reported some unintended outcomes, most often positive and having to do with higher than expected interest or participation in the project. The Campus Call is an example of this where a series of projects funded by the program to address gender-based violence on campus helped to create momentum as the issue received attention in the media. Provinces such as Ontario and BC moved to pass legislation requiring campuses to adopt sexual assault policies. Another example is the recently announced National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls which a few key informants noted was an inadvertent and unexpected achievement of WP funding to the Native Women’s Association of Canada.

According to several key informants, the WP’s increased focus on targeted calls as the preferred intake mechanism has had a potentially negative unintended outcome of mission drift among community organizations seeking funding, exclusion of other important issues and groups, and funding of weaker projects when there are few players within a given issue area. Finally, a few key informants also posited that the exclusion of national-level organizations, particularly those who had engaged in research and advocacy work, from eligibility for WP funding was perceived to have weakened the women’s movement overall.

4.4 Efficiency

Key Finding:

Variance between budgeted and actual expenditures: Over the four-year period under study, most of the budgeted allocation for the program was expended (underspending by 8% or $7.5M).

Administrative ratio: For every funding dollar provided by the program, $0.19 is spent on program administration.

Project leveraging: Almost all projects leverage internal resources and partner contributions, which typically represent one-third to one-half of the total cost of the project.

There is evidence that during the study period, the WP took important steps to improve efficiency of program delivery, including a Lean review of the application process, as well as other efforts to use electronic methods for the application process and review and tracking of projects. A high number of calls for proposals and announcements, the priority during the study period to reach out to new groups and increased expectations of projects translated into additional workload for staff which inhibited overall efficiency.

When resources permit, the program analyzes applications and project results to identify emerging issues and derive lessons learned. Lessons learned from program analyses, often echoed by funding recipients, confirm the importance of partnerships and engagement of senior decision-makers, as well as clients and communities, in the project.

Allocative efficiency

Efficiency measures for Gs & Cs programs typically include a comparison of the budgeted allocation and actual expenditures, and the administrative costs associated with the delivery of the program. Program financial data indicate that for each of the years under study, the program expended most of the Gs & Cs budgeted allocation. Over the four year period under study, the budgeted allocation was $96,994,413 and actual expenditures were $89,559,896, a variance of $7,434,517 or 8% for the program.

With respect to the program administrative cost ratio, for every $1 of actual funding provided by the program, $0.19 is spent on program administration.

The ratio for the current evaluation period is largely comparable to the efficiency ratio for the previous evaluation with variances from $0.16 to $0.20 from 2009–10 to 2015–16. We have excluded earlier years of the previous evaluation period (2007–2009) from the comparison because internal services were included as a component of salary and operational resources, and have been excluded as of 2009–2010.

Contextual factors influencing efficiency

Program documents and interviews with key informants identified a number of delivery efficiencies during the study period. In 2013–14, the program undertook a Lean exercise examining the application review process. The review recommended a team approach to reviewing applications, together with other process improvements to eliminate duplication, clarify roles and responsibilities, and train staff. On the basis of the first call for proposals in 2015 using the new approach, there were positive results in terms of the number of projects approved during the cycle (66% increase from the last call), a decrease in cycle time by 64% and a substantial decrease in the number of employees involved in the review, allowing staff to work on other priorities.

A potential downside of the adjusted process is a lack of knowledge and staff capacity to analyze the applications that are received. This issue was reflected in the comments from WP funding applicants, some of whom perceived a disconnect in the messages received during the preparation of their application and the results of their application. A peer review committee was implemented on a trial basis to review projects recommended for approval with a view to providing training to increase the quality and standardization of the analysis of applications and increase collaboration and teamwork across the WP.

Other efficiency improvements during the study period included:

- launch of SWC's online automated application system which has eliminated barriers to accessing information across the WP, and reduced processing time by up to two weeks (although the online application process presented difficulties for some applicants, a survey of external clients conducted by SWC found that almost nine in ten clients were satisfied or very satisfied with this tool);

- some assessment and performance measurement tools were updated to remove redundancy and reworked to apply to broader clusters of projects;

- a new Gs & Cs management system was implemented in 2013-2014;

- use of electronic consultations to review CI applications;

- development and publication of services standards; and

- reduction in lease/accommodation costs by decreasing its office space by 21% (costs of relocation will be re-paid from these savings over the next 8 years).

On the other hand, according to program documentation and key informant views, factors that detracted from program efficiency included more calls for proposals (during the study period 10 calls for proposals were issued compared to four calls during the last evaluation period); application approval delays associated with Ministerial Office processes; enhancements in the deliverables required of projects which placed additional demands on staff; a program priority to fund groups that were not currently receiving funding (“new”

groups), which increases workload for regional staff to provide more supervision and assistance; and a heightened priority on external communications and funding announcements.

Lessons learned

With respect to lessons learned, the program conducts periodic analyses of projects results to draw lessons learned. These can be specific to the context of the call or the specific project, and may identify overarching learnings from various lines of evidence. For example, emerging learnings included leveraging existing resources from previously funded projects to avoid duplication, integrate developed resources within on ongoing vehicle (e.g., curriculum) to increase reach and ensure sustainability, engage senior level decision-makers to reinforce priority of project objectives, leveraging of pre-existing and varied partnerships and, multiple intervention points.

Many of these findings are echoed by surveyed funding recipients. For instance, in an open-ended question about best practices or lessons learned to date from their project, funding recipients most frequently mentioned the importance of strong partnerships/engagement of partners and community/relationship building (30%). This was followed by involvement of the client group and/or the community in the design and execution of the project.

5.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

Relevance

There continues to be a strong demonstrated need for the WP. The program’s focus on violence, economic prosperity and leadership reflect areas where gender disparities continue to exist in Canada. WP objectives and expected results align with the SWC strategic outcome and federal government priorities as outlined in recent federal Budget commitments. Addressing issues of gender equality is appropriate for the federal government given the national scope of the issue and Canada’s commitments to gender equality in domestic and international charters and agreements. There is limited overlap and duplication between the WP and other programs at the provincial/territorial level or in the non-profit sector which are narrower in scope and granting capacity.

Design and Delivery

Design and delivery features identified as important in the program’s theory of change are generally in place and contributing to intended outcomes. Funding recipients are satisfied with many aspects of the program’s application process, although identify streamlining the application process which some find to be burdensome and complex, improving timeliness of approval decisions and strengthened communications as areas for improvement. Some delivery challenges may hinder achievement of program outcomes, particularly longer term outcomes. Program criteria that prevent funding of advocacy and research, as well as the three year maximum funding agreement were identified as detracting from projects’ potential to lead to systemic change. The evaluation gathered other feedback that pointed to the need for improvements in the program’s knowledge dissemination efforts

Effectiveness

The program promotes funding opportunities in a variety of ways, leading to far more applicants than can be funded. The emphasis on the economic calls during the period under study encouraged the program to work with new organizations serving entrepreneurs and women in the trades. The WP is providing projects with funding to develop a wide array of tools and supports. Tools and supports have been developed in all the pillar areas.

There is evidence that funded projects are providing opportunities to community-based organizations to use the tools and supports they produce. Projects use a variety of channels to disseminate their products, with a significant focus on web-based methods and social media. While most projects continue to make their products available after the WP funding ends, there is no central repository for sharing more broadly beyond the project’s own partners and networks.

A key success factor in fostering opportunities is projects’ effectiveness in forming partnerships, and the use of multiple components or intervention points. The WP application criteria are stringent in this area and evaluation evidence suggests that projects have been diligent and successful, undertaking partnerships in the design and more frequently, implementation phases. Many partnerships established for the WP project are new and funding recipients report that partnerships often outlive the project, as they continue to work with partners on other endeavours.

In terms of addressing the program’s longer-term outcome – communities and stakeholders advance equality between women and men – between one in three and four in ten closed projects that were sustainable reported operations, policy or practice change that fosters gender equality. Given the sheer difficulty of achieving systemic change, especially considering the WP funding parameters, this can be considered a significant success.

Intersectionality has increased in importance, both for the WP and its stakeholders. While a GBA+ approach does pose challenges for how the program is positioned in comparison to other federal partners, the organizations funded by the WP view the ability to account for multiple barriers as a key factor in facilitating project success.

In addition to the intended outcomes, the WP had positive unintended outcomes in several funding areas (e.g., campus violence and violence against Indigenous women) which exceeded expectations when the issue received increased attention in the media and by governments. Negative unintended outcomes are associated with the program’s eligibility restrictions and funding themes.

Efficiency

The WP’s annual budget allocation is fully expended each year. The cost to SWC of delivering $1 of Gs & Cs funding is $0.19. This has increased compared to the previous evaluation which calculated the cost of program delivery to be $0.13 for every $1 granted. Interviewees from the program suggested that this can be attributed to factors such as investments in new technology, multiple calls for proposals in new areas (e.g., entrepreneurship), as well as working with new organizations with a different profile. There is other evidence of improved efficiency of the program, however, due to a variety of initiatives such as a Lean review of the call for proposals process. Within the resources that available, the program is purposeful about collecting lessons learned from its calls for proposals and from projects for program improvement and determining emerging issues.

Recommendations

The program should continue to fund projects with a view to fostering systemic change. Key elements that were found in the evaluation to have the potential to support and increase systemic change include:

- continue to embed and clarify program understanding and expectations for sustainability of project impacts and systemic change within calls for proposals;

- embrace new flexibility to fund advocacy activities to complement the multi-component approaches that are currently being used by many projects to influence policy and institutional change;

- consider clarifying the WP’s logic model, and theory of change to support achieving sustainable systemic change; and

- explore opportunities to fund longer-term, higher value projects with multiple components to foster longer-term impact.

The program’s focus on systemic change is supported by program partners and stakeholders. It is a key distinguishing feature of the program in contrast to other service delivery interventions targeted to women that are offered by other jurisdictions or departmental authorities. The evaluation data indicate that the potential for systemic change is evident across many types of projects (across pillars, types of proponent organizations), although projects with multiple invention points are more apt to have led to changes at the level of policy or practice. Program stakeholders perceive advocacy and longer-timeframe/higher value projects to be important elements to support systemic change.

Increase efforts in knowledge translation/dissemination at the program level.

WP-funded projects have been very successful in generating a wide array of tools and supports. Broad awareness and take-up of these products is important to reduce duplication and amplify the impact of the WP investment. However, sharing of tools beyond the life of the project funding and beyond the funding recipient and their immediate partners is largely left to the projects themselves, which may not have the network or resources to share their tools more broadly. The WP has committed to developing a knowledge dissemination strategy which could be further elaborated, and include stakeholder engagement and ongoing support to extend projects’ work on the ground.

Enhance capacity across the program to support funding recipients through the project lifecycle to optimize their approach and efforts to achieve sustainable and systemic change.

The evaluation evidence suggests that while some projects have been successful in achieving objectives, others do not sufficiently understand and plan for sustainability of project impacts and can encounter challenges in achieving systemic change due to the complexities of the barriers they are trying to address and institutional resistance to change. SWC capacity (resources, staff capacities) to provide support over the project lifecycle has been constrained: only about half of funding recipients indicated that guidance and support from SWC during the project was a facilitating factor in the success of their project. As a Lean review is leading to some streamlining of the call for proposal process which has formerly absorbed a great deal of program resources, there is an opportunity to shift attention to the enhancing the capacity of the staff to provide meaningful ongoing support to projects during their implementation phase to reinforce approaches that drive change (e.g., working to develop communities of practice). Recent changes to the program mandate (e.g., eligibility of advocacy activities) also suggest the need for a renewed commitment to expanding staff capacity to effectively exploit this new program flexibility.

Status of Women Canada (SWC) concurs with the recommendations and each has been addressed in the Women’s Program Evaluation Management Response and Action Plan.

Appendix A: WP Theory of Change

Text version of Appendix A: WP Stages in Theory of Change

WP Stages in Theory of Change

- SWC determines the need for a programmatic response to address the issue of gender equality in Canada.